The NHS is set to offer the first gene-editing therapy in a revolutionary breakthrough for patients with beta thalassaemia. This innovative treatment involves extracting stem cells that produce blood, reprogramming them to correct the condition, and returning them to the patient’s body. This could potentially eliminate the need for lifelong blood transfusions every three-to-five weeks.

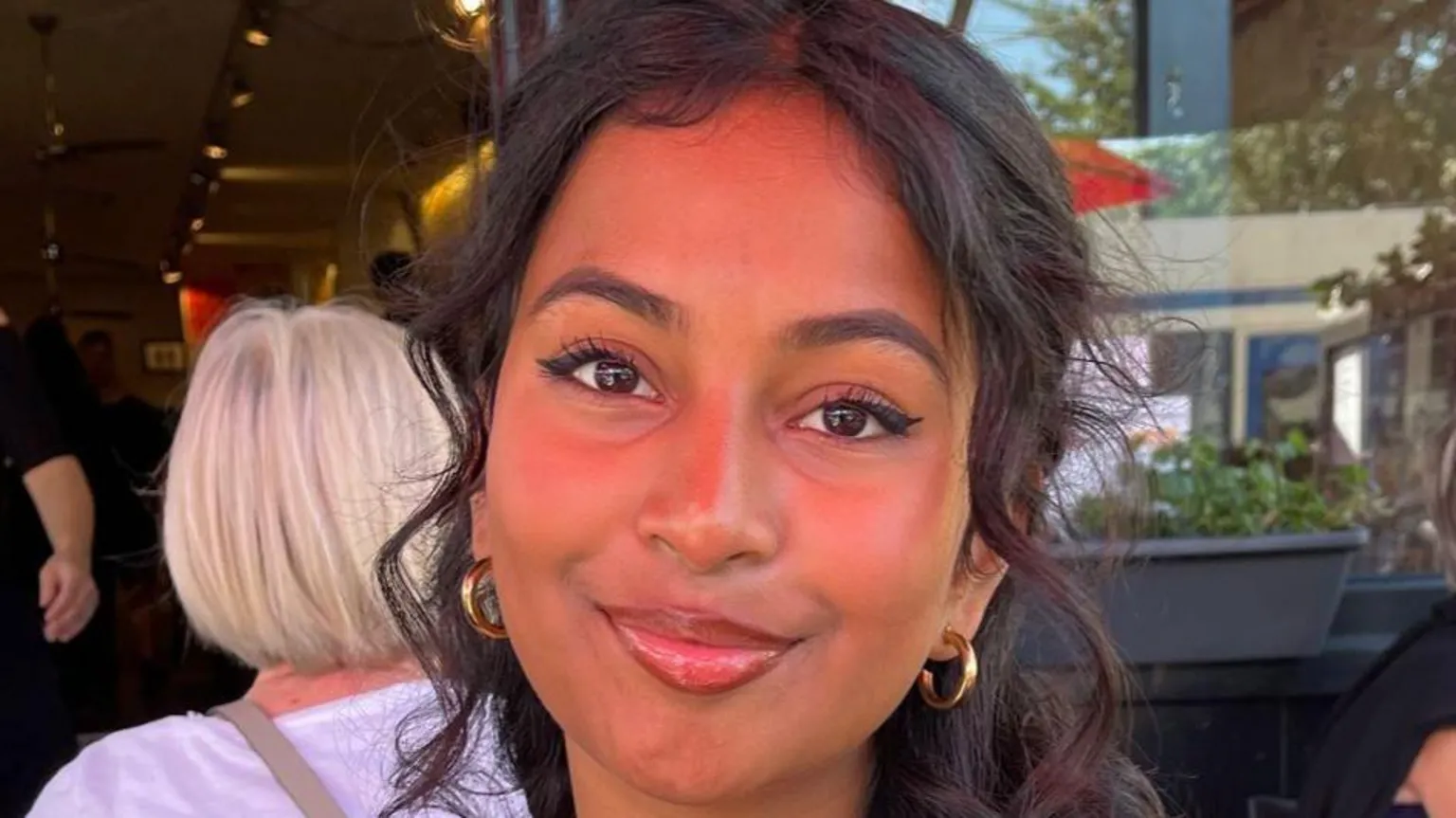

Beta thalassaemia is a genetic disorder that impairs the production of haemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells responsible for carrying oxygen throughout the body. This condition causes severe fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath, significantly reducing life expectancy. Kirthana Balachandran, diagnosed at three months old, experiences muscle and back pain and palpitations when walking uphill. “The idea of depending on transfusions for quite literally the rest of my life is daunting,” she says. “I constantly worry about the future.”

The therapy uses CRISPR technology, which won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2020. This tool functions like a satnav connected to scissors—one part targets the specific section of DNA, and the other performs the edit. Instead of repairing the genetic defect, the therapy disables a genetic switch called BCL11A, allowing the body to produce fetal haemoglobin, which is unaffected by beta thalassaemia.

The process involves harvesting stem cells that produce red blood cells, targeting the genetic switch in a lab, and then administering chemotherapy to eliminate the old stem cells producing defective haemoglobin before introducing the modified cells.

Abdul-Qadeer Akhtar, who participated in clinical trials in 2020, described the treatment as “challenging” but noted significant improvements in his health and activity levels post-therapy. “I have even taken up boxing and can travel more freely now,” he said. Data shows that out of 52 patients treated, 49 did not require another blood transfusion for at least a year.

While the long-term effects of this pioneering treatment are still unknown, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence has approved the therapy, with NHS England securing a deal to offer it at a reduced cost. The therapy, priced officially at £1.6m per patient, will be available at seven specialist centres within weeks. An estimated 460 people over the age of 12 are eligible for the treatment.

Amanda Pritchard, the NHS chief executive, hailed this as a historic moment for those with beta thalassaemia, offering a potential cure. Romaine Maharaj of the UK Thalassaemia Society described it as a “beacon of hope.” Additionally, negotiations are ongoing to extend the use of this therapy to treat sickle cell anaemia, another genetic disorder affecting haemoglobin.